An Interview with Gia-fu Feng

Transcribed by Shi Jing and Shi Tao

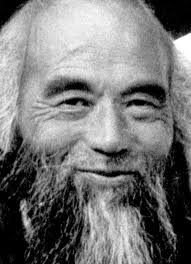

This article is an amalgamation of three separate interviews recorded with Gia-fu Feng some years ago before his death in 1985.

A Brief Background on Gia-fu Feng

Gia-fu Feng was born in Shanghai in 1919 into a fairly wealthy family of some influence. He was educated privately in his own home in the classics of the Chinese tradition, learning such things as the teachings of Taoism and Confucianism, art, calligraphy, poetry and tai chi. His family were followers of Taois. In the springtime, they traveled to a temple in the mountains of Hang-Chou for the spring festivals. When Gia-fu stayed at the temple for longer periods, he was trained in Taoist practices. He continued with his education by going to Beijing University where he gained a bachelor’s of arts degree.

Shortly after, in 1947, the communists took over China. Gia-fu left the country taking, in his own words, “The last boat out of China” and traveled to America. After further study at the University of Pennsylvania, where he received a master’s of arts degree, he became involved in teaching Taoism. First he taught at the American Academy of Asian Studies, followed by the Esalen Institute, then moved to Colorado and started his own center-called Stillpoint Foundation-in Manitou Springs. There he worked on his well known translation of the Tao Te Ching. He also began to teach in Europe; it was on one of those trips in 1978 that Alan Redman (Shi Jing) became his student. Gia-fu was a real “Man of Tao,” unpredictable and wild. Alan once described him as a character who had jumped straight out of the pages of a Chuang Tzu story!

How did you get involved in teaching Taoism in America?

By 1950, at age 31, I was forced to be a “dropout” and started wandering all over the country. By the early fifties I was on the West Coast and by chance met Alan Watts, Jack Kerouac and the North Beach San Francisco crowd. Later on, of course, I joined the Esalen Institute where I met Fritz Pearls, Abraham Maslow and Bishop Pike.

What sort of things were you doing at Esalen?

I was doing my own things from the Taoist tradition, like acupressure, the ancient way of moving chi in the meridians, the relationship between the muscles, emotion and well being. I did some movement and tai chi to help in family therapy sessions and so on. The important thing in the sixties was that there was a great deal of interest in the integration of body, mind and spirit. This is exactly what Taoists try to do. So by 1966 I started my own center called Stillpoint, a Taoist retreat with Taoist philosophy put into practice, mainly centering on the flowing of chi.

Do you see this as the central aspect of many of the Taoist practices and arts, such as meditation or calligraphy?

Yes, and calligraphy especially is a very true manifestation of chi. We can maybe translate the word chi as “emanation” or “energy” or “breath,” which is physical. So in order to be a good painter you must have a good flow of chi, which is what tai chi is all about, making your chi flow. Your chi is centered in the belly, in the tan tien, a couple of inches below the naval; it is the center. So during meditation we always try to put our mind in the belly, so to speak, to get out of the mind and come back to the body-bodily center, a physical manifestation of the Tao.

Meditation in Taoism is when you hit rock bottom. We call it the great stillness, or sometimes I translate it as the great certainty. Taoist meditation is to reach the stage of a great physical certainty. Taoist meditation is very physical. A lady asked me, “What is Taoist meditation?” I said, “Holding on to the center, literally holding on to your tan tien and clinging to the chi, clinging to your breath, your chi, your life energy.” Your breath is from the cosmic energy and you literally transform yourself, not by your own breath but the breath that comes from the cosmos, which brings a sense of being reborn. I was telling Alan just a minute ago, the Tao is everywhere, it is manifested in your tan tien and therefore you are the Tao. You are the microscopic version of the Tao. It’s physical. You actually can feel the Tao rest in your belly. Your whole body is settling in stillness. You reach the rock bottom like a rock in the ocean. You really are a rock because you don’t have to use mind. No interference with the mind.

Where do the basic teachings of the Tao originate?

I think all of Taoism is a formation of the old verbal tradition and I think it’s real Chinese stuff. There is no foreign influence at all in the Tao Te Ching or the I Ching of course. The I Ching is also a formation of old wisdoms come along by word of mouth. Duke Chou is the founder or the one who really put it into words in a book. So I tend to think that Duke Chou, together with Lao Tzu, are the formation of the ancient teachings of China, of the northwestern part especially, where civilization was born thousands of years ago.

Could you talk about the Tao Te Ching and some of the main teachings that it is expressing?

Certainly. If we look at the Tao Te Ching it seems to me that the basis of these verses is a thread of respect for the primal nature:

Chapter 20

Give up learning and put an end to your troubles.

Is there a difference between yes and no?

Is there a difference between good and evil?

Must I fear what others fear? What nonsense!

Other people are contented, enjoying the sacrificial feast of the ox.

In spring some go to the park and climb the terrace,

But I alone am drifting, not knowing where I am.

Like a newborn babe before it learns to smile,

I am alone without a place to go.

Others have more than they need, but I alone have nothing.

I am a fool. Oh, yes! I am confused.

Others are clear and bright,

But I alone am dim and weak

Others are sharp and clever,

But I alone am dull and stupid.

Oh, I drift like the waves of the sea,

Without direction, like the restless wind.

Everyone else is busy,

But I alone am aimless and depressed.

I am different.

I am nourished by the great mother.

The last sentence really means in Chinese “I prefer to eat mother.” Now my first version is “I suck off my mother” and then of course I am told they cannot print this, so it says “I am nourished by the great mother.” It’s just as good. Here we touch on this emphasis of giving up cultural conditioning and preconceptions and returning to the primal, returning to the little babe, returning to the mothers’ breast.

Chapter 1

The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao.

The name that can be named is not the eternal name.

The nameless is the beginning of heaven and earth.

The named is the mother of ten thousand things.

Ever desireless, one can see the mystery.

Ever desiring one can see the manifestations.

These two spring from the same source but differ in name;

This appears as darkness.

Darkness within darkness.

The gate to all mystery.

So there’s a great deal of emphasis on the nameless, on the darkness, on the primal chaos, so to speak. It is strongly emphasized that the Tao cannot be told. It is a kind of non-duality beyond the opposites and the unknowable and we have to see that our conscious mind is not the ultimate. In this chapter we also see the relativity in Taoism:

Ever desireless, one can see the mystery.

Ever desiring one can see the manifestation.

This is the only translation that has that flavor. In Chinese it literally says “Constantly no desire to see the mystery or constantly have desire to see the obvious.” But I said, “Ever desireless, ever desiring.” It is two in one, meaning the Tao is beyond desireless or desiring. Ever desiring and ever desireless is one and the same thing. You can’t really be desireless without desire. Put it right on the line. This is the crux of Taoism-very paradoxical. What do you mean, I have no desire? Of course I have!

Then the theme of relativity continues in the second chapter; this brings in the Taoist concept of yin and yang. The Taoists usually talked about yin and yang, weak and strong. When you have yin you must have yang, when you have yang you must have yin; they compliment each other. For instance you cannot succeed without failure. If you always succeed you can’t succeed anymore. You’ve got to have some failure in order to succeed-it’s all relative. Perhaps it’s a good way to relieve anxiety. Today, for instance, we are so troubled with anxiety. Perhaps this is the way to deal with it.

Chapter 2

Under heaven all can see beauty as beauty only because there is ugliness.

All can know good as good only because there is evil.

Therefore having and not having arise together.

Difficult and easy compliment each other.

Long and short contrast each other;

High and low rest upon each other;

Voice and sound harmonize each other;

Front and back follow one another.

Therefore the sage goes about doing nothing, teaching no-talking.

The ten thousand things rise and fall without cease. Creating, yet not possessing,

Working yet not taking credit.

The work is done, then forgotten.

Therefore it lasts forever.

So you almost come to a state of mind that is non-judgmental, a state of suchness. Nothing is set, you notice; it’s all in flux and you can stay with your experience without rejecting or accepting. If you’re angry, be angry. If you feel shitty, be shitty. If you’re depressed, be depressed. You really see the pure light is beyond accepting and rejecting. The Taoist mantra would be, “There’s nothing lacking. Nothing in excess. It is only because we accept and reject that we know not the suchness of things.”

Alan Watts mentions this all the time. If you’re long bamboo, you’re long bamboo. If you’re short bamboo, you’re short bamboo. Everything compliments everything else. Don’t get messed up about anything. It’s absolutely basic when you see everything from the Tao. No matter what you do there’s no right or wrong. At the moment all that counts is here and now, you and I, what works, what doesn’t work. So this is a beautiful chapter.

Now “Teaching no talking.” Mitsui, our internationally famous yogi teacher from Japan, was talking to me yesterday. She spent ten years with master Oki in Japan. She says, “Master Oki never taught me.” The Americans, who were also there, went crazy! “What do you mean-we spend all this money here and you don’t teach us!” But everybody there in the dojo knows how to put in an acupuncture needle with absolutely no teaching. They know how to do therapy; they’re a healing center. Mitsui herself had a breast disease which was completely healed without ever being told by master Oki “I’m going to heal you.” Nothing was said and it just healed by itself. So this is teaching by not teaching. You don’t teach them; that’s a teaching also! Refusing to teach is a teaching.

This is traditional of many Japanese and Taoists, even more now in Tokyo than in Peking or Shanghai, absolutely, I vouch for it. Japan has a great simplicity. There is the little tea house where you have to stoop to get inside, the beautiful gardens, the Zen gardens. You know I was in Japan and they gave me a block of ink in an ink stone. It was so narrow and I had to prepare the ink in this. But in China they are big! I have one. A big, huge rock, and there you grind with a big huge ink! But in Japan everything is small and simple. In absolutely every house you go to there’s a Tokonoma. This is an alcove in the wall of the room, with a statue or painting of some kind. So this is the only furniture in the whole room of empty tatami mats. The beauty, the art is Japanese, pure asthetics, you know. So I have such liking for all Japanese teaching in this country, especially for Sabro Hasegawa. He actually was Taoist and a great artist from Japan. He died in 1958, in San Francisco, which Alan Watts mentioned in his book “Tao-The Water Course Way.” He was a great Taoist. He asked me once, “What’s the most delicious food you ever had?” I said “Well, chop suey.” He said, “Yeah . . . just plain rice.” (Gia-fu laughs like mad.) That’s the most delicious food you could ever have! Just plain rice! Pure, blank, but it must be cooked grain by grain.

Mitsui was telling me about Shintoism, which she studied in Japan. She told me yesterday, on a walk, that in Shinto you have to soak in water in the sea every day. Even if the water is cold you have to go in there. You must soak and purify. Another thing they do is look in the mirror every day and see yourself as God. You have to face the mirror and see yourself as a god. And these two things she told me were very, very significant. You literally have to go down to the ocean of cold water to purify yourself, not just to think about it. The trouble with Western man is that everything is intellectualized.

So now we talk about wu wei which means non-action, but really better translated as non-interference. Wu wei is wei. Meaning non-action is action. When you’re totally quiet, your organ really manifests itself into action without you even knowing it. And that’s the real action.

Chapter 48

In the pursuit of learning, every day something is acquired.

In the pursuit of Tao, every day something is dropped.

Less and less is done

Until non-action is achieved.

When nothing is done, nothing is left undone.

The world is ruled by letting things take their course.

It cannot be ruled by interfering.

The action of non-action is a true action without any anxiety and without any competitive ideas, without wanting to conquer anything, so you become a total action of your organs. Now I always want to bring it down to the physical level. What your organ really feels.

Do not seek fame.

Do not make plans.

Do not be absorbed by activities.

Do not think that you know.

Be aware of all that is and dwell in the infinite.

Wander where there is no path,

Be all that heaven gave you,

But act as though you had received nothing.

Be empty, that is all.

The mind of a perfect man is like a mirror.

It grasps nothing.

It expects nothing.

It reflects but does not hold.

Therefore the perfect man can act without effort.

Chapter 43

The softest thing in the universe

Overcomes the hardest thing in the universe.

That without substance can enter where there is no room.

Hence I know the value of non-action.

Teaching without words and work without doing

Are understood by very few.

In translating this into English we lost the real punch line. “Teaching without words and work without doing are understood by very few.” There is no punch to it, but in Chinese it says “Wordless teaching, actionless benefit-the benefit of no action, the teaching of no words. All under heaven seldom get into it.” That’s the real translation. Not “understood by very few.” So I want to do a new edition. “Teaching of no words, the benefit of no action, all under heaven is seldom into it.”

Chapter 15

The ancient masters were subtle, mysterious, profound, responsive.

The depth of their knowledge is unfathomable.

Because it is unfathomable,

All we can do is describe their appearance.

Watchful, like men crossing a winter stream.

Alert, like men aware of danger.

Courteous, like visiting guests.

Yielding, like ice about to melt.

Simple, like uncarved blocks of wood.

Hollow, like caves.

Opaque, like muddy pools.

Who can wait quietly while the mud settles?

Who can remain still until the moment of action?

Observers of the Tao do not seek fulfillment.

Not seeking fulfillment, they are not swayed by desire for change.

“Observers, observe” actually would be the best translation. They who have, who carry out, who guard against the Tao, do not seek to be full. You’re not full, so you cannot be worn out and you have no desire for change. Then you can be renewed. So fulfillment is not really the right word, not to seek to be full, but to succeed actually is better. “Who can wait till the mud settles?” Let dust settle before you act. Yeah! It’s too bad; it’s very poetic in Chinese. Here we said, “Alert, like men aware of danger. Courteous, like visiting guests. Yielding, like ice about to melt. Simple, like uncarved blocks of wood. Hollow, like caves. Opaque, like muddy pools.” All this charm is lost in English. But still, it’s better than nothing. And then, “Who can remain still until the moment of action?” Again there is the meaning of some kind of divine accident here also. You really are very open and still until the moment that you’re moved to act. Again, back to the emptiness, total openness, to totally listen to your own center with no preconceived idea. Now I think that emptiness is the essence of Taoism. Many chapters start with “be empty.” The empty vessel is used but never filled. Chapter 11 is very potent about emptiness:

Chapter 11

Thirty spokes share the wheel’s hub;

It is the center hole that makes it useful.

Shape clay into a vessel;

It is the space within that makes it useful.

Cut doors and windows for a room;

It is the holes that make it useful.

Therefore benefit comes from what is there;

Usefulness from what is not there.

This is again the basis for non-action. It is the holes that make it useful. So leave something undone, you know, do not try to do everything, and don’t interfere. It is only when you do not interfere that a divine essence will take over. So no interference and be empty.

You’ve mentioned Alan Watts several times and I know that you’ve been with him when he was teaching. What was he like to be with?

You see Alan Watts was very creative. When he drinks he’s very clever. He was in a class, you know, at night time, he was all drunk. But his lectures were never boring. He was a tremendous entertainer. He said, “I’m an entertainer, I’m no Buddhist philosopher.”

Alan Watts actually died from alcohol, didn’t he?

Oh yeah. At that time he drank whisky by the bottle.

But how could that tie in with the Tao?

That’s from the Tao! The fact that he drank is totally in tune with the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove-his utter disregard for convention. One of the sages, a famous poet called Liu Ling, had a servant who followed him carrying a jug of wine and a spade. In this way he always had some wine to drink and his servant would be ready to bury him if he dropped dead during a drinking bout! It’s in the Tao. So Alan Watts’ drinking is quite Taoistic.

Have you experienced that people come into tai chi as physical exercise and through the practice of it have come to understand and be interested in the philosophy?

Yes. Oh yes. There is definitely a great demand today. Young people want to learn kung fu or want to fight, they want to achieve a certain technique and power. This is always the preoccupation of young people today. “How can I have power?” like such and such guru or whatever. So people use physical exercise as an expression for their own aggression and then finally after they empty their aggression they come to the philosophy of the Tao, and they really find peace. There is a place for something that is violent, that is physical, that uses great strength and so on, but this is only a step toward the ultimate integration of body and mind. If you only follow the forms you lose the essence, and essence can only be experienced by yourself and through yourself. But now of course the gurus are here to demonstrate that they have reached a certain stage, like a master, a tai chi master so to speak. Actually there is not an outside master, but you can see some essence of the practice of Taoism in some people who are fully on their path. There is a saying in China that of every three men walking there is always one who is my teacher. I would say every man is my teacher.

And in this way nature is also your teacher?

Nature especially. You become so empty that you find all experiences are a learning opportunity. I live by the Rocky Mountains where there is a trail to one of the peaks. I spend hours there every day, in the afternoon usually. I walk maybe as much as seven hours and I’ll disappear into nature and just experience my own Tao. You know I can’t do it with many people around. I have to be alone and I have to be into nature. When you walk down the street it’s a different affair all together. You see everybody can experience that. There’s nothing like being with nature. So the great experience is interwoven with nature. It really proves that we are a part of nature. Taoism has always held that we are a part of the cosmic organ or the organism and that a human being is a microscopic version of nature. We see that a waterfall is pretty, but we see a garbage dump is not pretty. Why? Because the waterfall is in me. There is a waterfall in every human being. That’s why we see that nature is beautiful.

It sometimes feels as though we have a garbage dump within us too.

But that’s in me too! Yes. Oh yes. Now another thing is that Taoists would never deny anything human, including our bad parts. So I was sometimes called a rogue. Why? Because I indulge my instincts perhaps. I don’t deny my instincts.

So it is important to become comfortable with yourself, comfortable with others and comfortable with nature. Taoists are very much interested in the coming and going of the seasons, in the process of nature, and that really reminds me of a NBC show I did just yesterday. It was a one hour talk show and we played it this morning after they all finished and, although I have been in the United States for thirty years, all I see is my father in my own expression. My way of talking, my gesture is totally Chinese. I have not Americanized at all, even though I can pronounce words better than I could thirty years ago. All the essence is so Chinese and so I almost give myself a revelation, but I cannot change, meaning the nature takes over. Now we can’t speed up a plant – the seasons just come. Nature cannot be hurried. It takes it’s course and it is the same with human beings. The same with our growth even. So we can certainly learn something from the east – to reach the simple, the comfortable, the natural, the real living so to speak. We don’t want to be zombies! We want to live our lives to suit our human needs, our organic needs at that. To listen to our own organs, listen to our own flow, listen to our own chi. Now this is very true if you’re an artist, or a writer or, a painter. Just like Picasso says, “I can’t help painting. I don’t want to be a big huge name, but I can’t help doing it.” Once he listens to his own organs he has to paint. So his painting is organic, it’s from his true nature. Love, in the Chinese language is a true expression of the organs, meaning you are totally naked, your organ is perfectly functioning, and this expression we say is ‘love’. So this is a totally organic concept of the universe. Beneath all that we know there is a Tao that’s working silently, working without words, that really runs the whole universe or manifests in ourselves. I think one of the contributions of Taoism is to put the spiritual level into our pragmatic evcryday life, which is chi. You can get in touch with your centre by physically feeling the flow

The article was originally printed in the Dragon’s Mouth, the magazine of the British Taoist Association. 16 Birch View Epping Essex CM16 6TJ England.